From the Autumn 2023 factor of Dwelling Chicken mag. Subscribe now.

Sarah Sortum has a photograph of her grandparents receiving a conservation award in 1973 for planting bushes throughout their ranch within the japanese Nebraska Sandhills.

“In my grandparents’ era they have been in point of fact inspired by way of conservation methods to plant bushes,” says Sortum, who now is helping run that very same family-owned acreage, referred to as the Switzer Ranch. “Take note, that is the Arbor Day state. That’s a lifestyle in Nebraska, planting bushes.”

The bushes, essentially local japanese redcedar, be offering coloration and visible aid from the unrelenting horizon of prairie. Their dense branches and evergreen needles supply a windbreak and natural snow fence to offer protection to the abode, and a digital “out of doors barn,” in Sortum’s phrases, for calves in spring.

“Now we now have those gorgeous, mature cedar windbreaks, and they’re treasured to us,” she says. “However now we now have all this seed supply.”

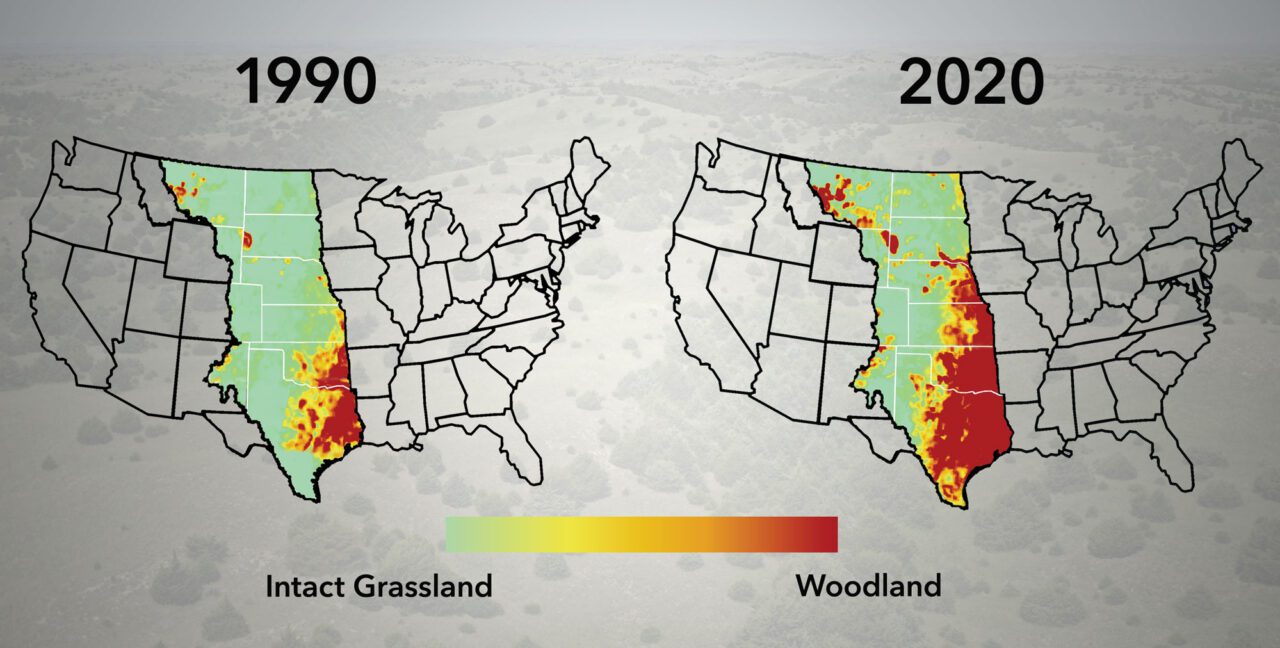

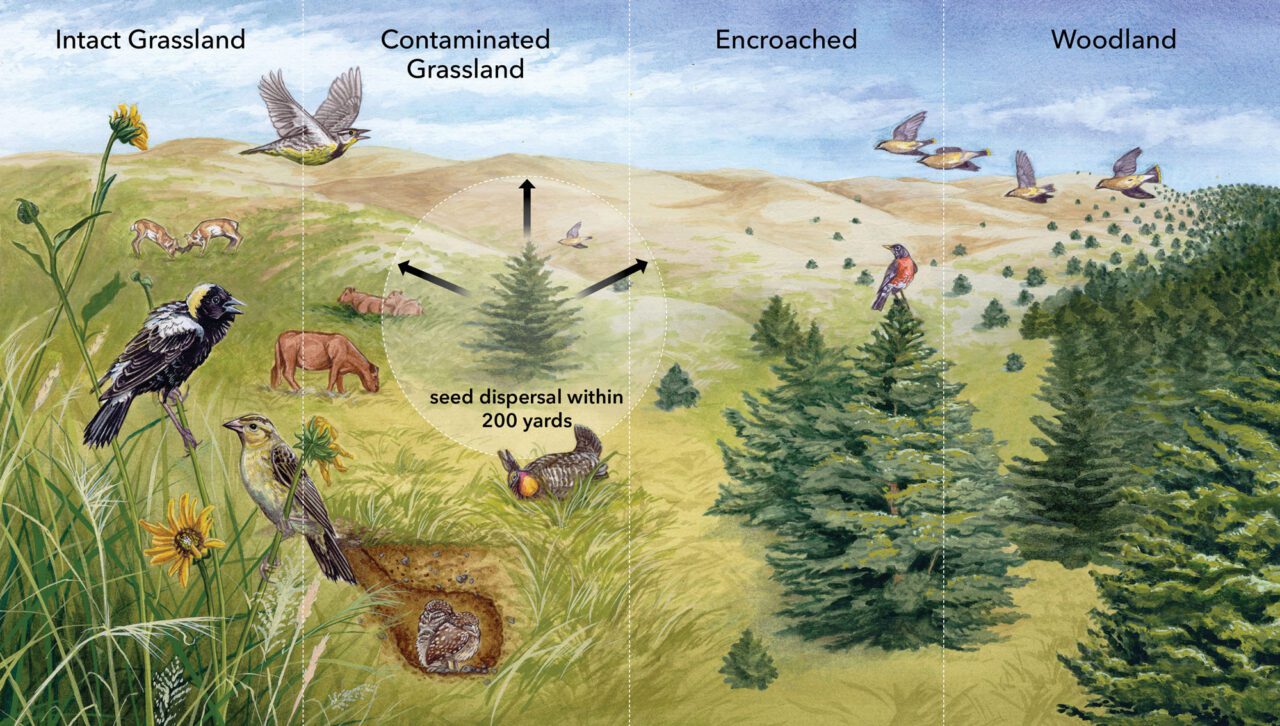

Analysis from the College of Nebraska–Lincoln presentations that that seed supply—the totally grown redcedars bursting with tiny cones on the ends in their evergreen branches—can propagate a wave of cedar seedlings that unfold out a pair hundred yards clear of the mother or father tree. Two generations after her grandparents planted them, the ones redcedars are spreading out from the abode and windbreaks, developing an ungovernable entrance of forest. And it’s now not simply the Switzer Ranch. The similar factor is going on all over the Sandhills—and throughout a lot of the central Nice Plains.

The advancing wall of conifers, dubbed “the fairway glacier” by way of Oklahoma State College rangeland ecologist David Engle, threatens the very lifestyles of grasslands—and grassland birdlife. Consistent with Engle, the woody encroachment, as ecologists name it, “is converting endemic avifauna to an extent similar to that of the Pleistocene glaciation.”

In Nebraska’s Sandhills, the transformation is scaring the bejeezus out of ranchers, fowl biologists, and everyone involved that the conversion of grassland to forest will consume up habitat for prairie flora and fauna, and doom the ranching way of living. Says Sortum, “The largest not unusual problem we’ve were given is the redcedar.”

The answer—or a minimum of the resolution that ranchers and conservationists are aiming for—is a joint effort to make use of mechanical tree elimination and prescribed fireplace to overcome again the development of bushes and keep land for livestock and prairie flora and fauna.

“We in point of fact see it as the most important danger to the Sandhills ecosystem,” says Shelly Kelly, govt director of the Sandhills Process Drive, a rancher-led group that’s main the combat towards redcedar on personal lands.

And in Nebraska, nearly all land is personal land. With out the assistance of landhomeowners, Kelly says, not anything a lot might be in a position to offer protection to ranching, the prairie, or grassland birds from the bushes.

“Onerous-pressed to discover a unmarried tree”

The Sandhills occupy more or less 20,000 sq. miles in north-central Nebraska, 1 / 4 of the state. Shaped as shifting, rising dunes of wind-driven sand, the hills stabilized as lately as 1,000 years in the past and as of late are capped by way of mixed-grass prairie. Recognized by way of locals and ecologists as “uneven sands,” the low however steep hills are susceptible to slumping spaces referred to as “catsteps” and wind-caused “blowouts” of uncovered sand.

The Sandhills border on arid—23 inches of annual precipitation within the east fading to 17 inches within the west, dry sufficient that the panorama teeters between prairie and forest. But underneath all that sand and dry-prairie grasses lies the prodigious Ogallala Aquifer, probably the most international’s greatest shops of groundwater and supply of about 30% of agricultural irrigation in the US. And as a grassy biome, the huge Sandhills are globally significant—probably the most greatest last intact temperate grasslands on the planet, in line with Melissa Panella, supervisor of the Flora and fauna Variety Program for the Nebraska Recreation and Parks Fee. Consistent with the Fee’s state flora and fauna motion plan, the Sandhills are a hotbed for the so-called Tier I at-risk Species of Biggest Conservation Want, together with Baird’s Sparrow, Burrowing Owl, Ferruginous Hawk, Loggerhead Shrike, Brief-eared Owl, Sprague’s Pipit, Whooping Crane, and Lengthy-billed Curlew. Actually, the western Sandhills is without doubt one of the “ultimate number one strongholds” of curlew, says Joel Jorgensen, nongame fowl program supervisor for the Recreation and Parks Fee.

When Eu explorers first surveyed the land, infrequently a tree might be discovered. “It is advisable shuttle throughout all of the Sandhills with out seeing a tree,” says Dillon Fogarty, researcher and program coordinator for running lands conservation on the College of Nebraska–Lincoln. “They have been tucked in on only some move banks.”

In the ones days, the drive at the panorama maintaining bushes in test was once fireplace—some set naturally by way of lightning, however maximum by way of busy people with an eye fixed towards recreation and land control. The earliest population of the Plains, says Fogarty, “actively formed their atmosphere to create an atmosphere that they may thrive in.

“Indigenous teams had been the usage of fireplace and shaping ecosystems for thousands of years. And our flora and fauna species within the Plains advanced with techniques that burn ceaselessly.”

As settlers and their executive pressured tribes such because the Pawnee, Lakota, and Plains Apache from the Sandhills, in addition they got rid of the competitive use of fireside to regulate the panorama. Actually, the rookies attempted to stop any fireplace in any respect. Below this new regime, the scrappy however fire-vulnerable japanese redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) was once in a position to project out from the steep slopes and canyon partitions alongside prairie streams and onto grasslands, the place its sexy powder-blue seed berries have been ate up and expelled by way of the likes of Cedar Waxwings and Yellow-rumped Warblers. Redcedars aren’t a fast-spreading invasive species in their very own proper; some 95% of a cedar’s seed manufacturing in a 12 months falls inside of simply 200 yards of the seed supply, in line with Fogarty’s analysis. However with out fireplace to burn off their advances, the bushes emerged from their refugia and unfold around the prairie.

And that’s now not all. Settlers unwittingly aided the destruction of the prairie by way of planting extra bushes—even making an arranged effort of it. Within the nineteenth century, J. Sterling Morton, a informationpaper editor in Nebraska Town and later secretary of the Nebraska Territory, enthusiastically promoted tree planting. After statehood, he proposed a vacation to inspire electorate to plant bushes. At the first American Arbor Day on April 10, 1872, fans planted one million bushes in Nebraska that day on my own. For many years, civic organizations and government businesses persevered to plant bushes and advertise tree planting.

It wasn’t a troublesome promote. The newcomers to the prairie (many settlers with Eu heritage have been forest other folks by way of ancestry) discovered convenience and sensible makes use of for a couple of bushes, from firewood to fence posts. As the ones bushes have matured and produced seed, that 200-yard growth radius of seeds and seedlings continuously expanded, era by way of era.

“So we now have an important a part of the Plains now this is lined by way of bushes and their seed dispersal,” Fogarty says.

And that suggests the bushes are at the transfer. Consistent with 2022 analysis published within the Magazine of Carried out Ecology, tree quilt has higher 50% around the rangelands of the western U.S. within the ultimate 30 years. The creeping woodlands threaten open prairie, prairie flora and fauna species, and the ranching trade. In addition they building up the probabilities of uncontrollable wildfire.

In Nebraska particularly, just about 8 million acres of intact grasslands are estimated to be in danger from woody encroachment, in line with the Nebraska Nice Plains Grassland Initiative of the federal Herbal Assets Conservation Carrier.

“We’re dropping the fight,” says Fogarty.“ So long as we’re having the fad of woody encroachment that’s proceeding to extend…longer term that suggests we’re now not in a position to maintain our grasslands.”

“That’s sacrilegious in Nebraska”

Sarah Sortum’s great-grandfather and his brother first got here to the Sandhills within the early 1900s as marketplace hunters, capturing prairie-chickens and Sharp-tailed Grouse to send by way of rail to restaurants in Omaha. The brothers determined to stick and homesteaded on adjacent sections of land.

“And we’ve been right here ever since,” says Sortum. She grew up at the ranch, left awhile together with her husband to regulate a high-end visitor ranch in Colorado, after which returned to sign up for her older brother within the Sandhills.

These days the Switzer Ranch grazes red meat livestock and operates a ranch-based tourism trade referred to as Calamus Clothing stores. Coyotes, badgers, porcupines, bobcats, and each mule deer and whitetails roam the valuables. Sortum additionally ceaselessly sees the vintage birds of Nice Plains grasslands: Grasshopper Sparrows, Bobolinks, Jap and Western Meadowlarks, and quite a lot of sandpipers and herons. Larger Prairie-Chickens and Sharp-tailed Grouse, descendants of the birds hunted by way of her great-grandfather, proceed to occupy the ranch. The chickens keep on with the low meadows and benches on the base of hills. The sharptails hunt down the sparser grass, plum thickets, and patches of leadplant at the “giant, uneven hills.” Sandhill Cranes every now and then fly over on migration, regardless that they hardly land. Says Sortum, “That’s more or less how we mark our spring and fall.”

Two birds not unusual now, however that Sortum hardly noticed rising up, are Blue Jays and Northern Cardinals. Each species consume redcedar berries and thrive within the advancing woodlands. She says that two decades in the past, when a host of little bushes began coming out of the pasture on her kinfolk’s ranch, “no one in point of fact concept an excessive amount of of it.”

“No one in point of fact were given excited. And no one went to chop them, as a result of that’s sacrilegious in Nebraska,” says Sortum. “And so it were given clear of everyone. … Rapidly you get up sooner or later and pass, ‘Oh my goodness, that is beginning to lower into my base line as a result of take a look at how a lot grass I’ve misplaced.’”

Sortum wasn’t the one one stuck by way of wonder.

“One of the crucial issues that has been a killer within the Sandhills and different portions of the Plains is a disbelief that woody encroachment can occur,” says Fogarty. “Other folks within the conservation group and another way have lengthy concept that the Sandhills is simply too dry, too sandy for encroachment, that it simply couldn’t occur in that panorama.”

However that’s now not true, he says: “Even within the western Sandhills, if we now have a seed supply, we now have unfold.”

“Final analysis is that we’re a prairie state”

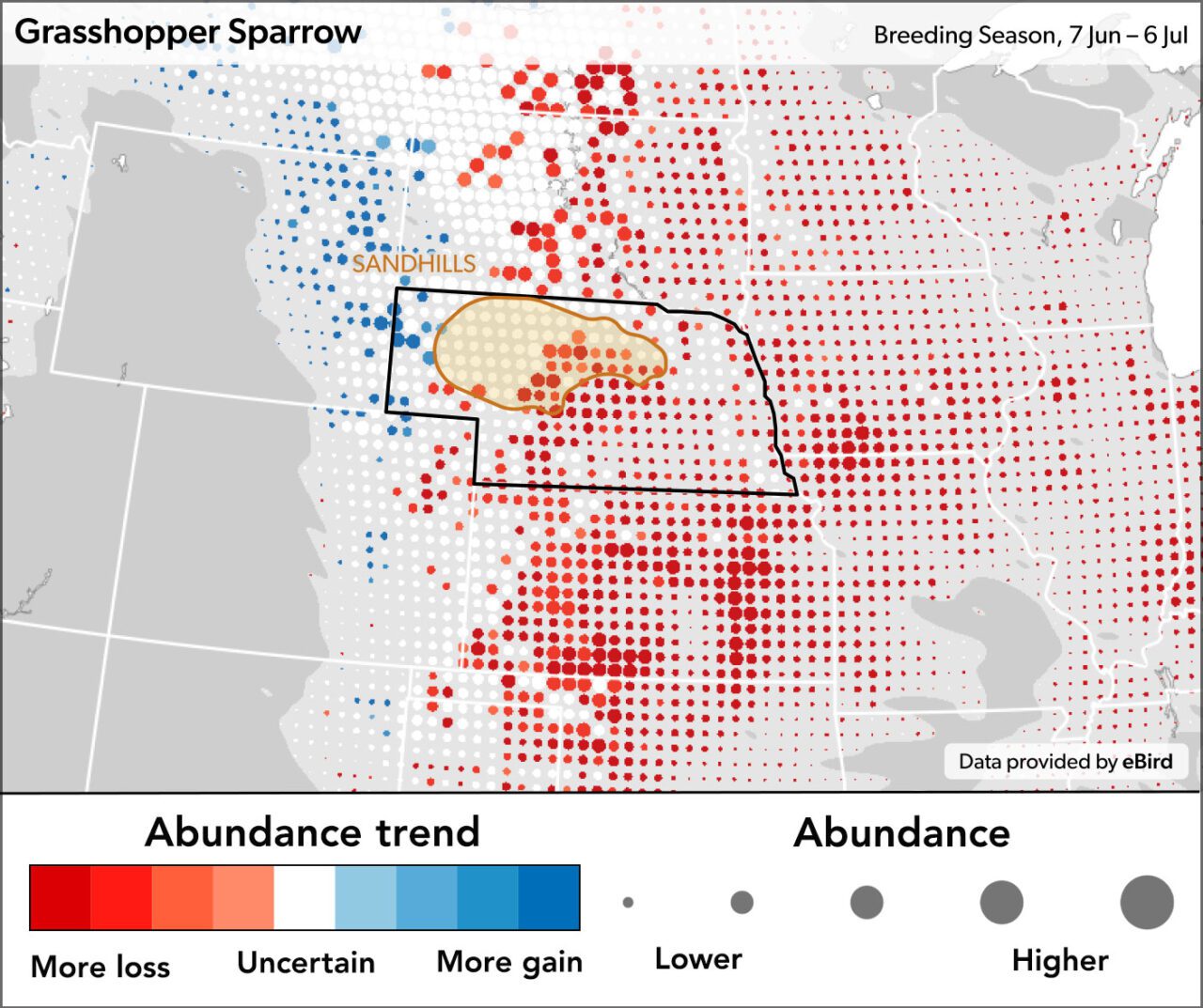

The lack of open prairie threatens a number of grassland birds, and the illusion of only some bushes in line with acre is sufficient to purpose some fowl species to disappear. Consistent with quite a lot of research within the Sandhills and close by grasslands, Grasshopper Sparrows are maximum abundant when the redcedar cover is not up to 10% by way of space, and so they disappear completely when woodlands quilt a 3rd of the world.

Around the continent, grassland birds are in disaster. Within the landmark 2019 learn about revealed in Science that confirmed North The usa had misplaced 3 billion birds since 1970, grassland birds have been by way of a ways the most important losers—with a complete inhabitants decline exceeding 50%.

Consistent with Joel Jorgensen, the nongame fowl program supervisor for the Nebraska Recreation and Parks Comchallenge, the Sandhills and surrounding space are the most efficient position to take a stand and spark a turnaround for grassland fowl populations.

“I believe the base line for me is we’re a prairie state,” says Jorgensen. “If we’re going to preserve maximum of our grassland birds, that is the world, the Nice Plains, the place we wish to center of attention that spotlight.”

However the lack of birds isn’t the one, and even crucial, worry of other folks residing within the Sandhills. According to that 2022 learn about within the Magazine of Carried out Ecology, the 50% growth of tree quilt throughout U.S. rangelands—consuming up a space of grasslands just about the dimensions of South Carolina—has charge farm animals manufacturers between $4 billion and $5 billion because of the lack of grass and forbs for forage.

If we’re going to preserve maximum of our grassland birds, that is the world, the Nice Plains, the place we wish to center of attention that spotlight.

Joel Jorgensen, nongame fowl program supervisor for the Recreation and Parks Fee

One of the crucial authors of that learn about—Dirac Twidwell, a rangeland and fireplace ecologist on the College of Nebraska–Lincoln—says there are lots of different prices to other folks residing on this area, too. For instance, he issues out how redcedar woodlands refuge animals comparable to white-tailed deer, turkeys, and coyotes that act as reservoirs and transporters of ticks, particularly the lone big name tick—a vector for a number of severe sicknesses that afflict people.

And satirically, Twidwell says the absence of fireside in Nebraska’s Sandhills can building up the chance of critical wildfires that endanger other folks and belongings, as woody tinder builds up on a slightly arid panorama.

The threats from redcedar also are creeping into state schooling investment. The Nebraska Board of Instructional Lands and Price range, the most important landowner within the state, rentals a lot of its acreage as rangelands for farm animals grazing as a supply for tens of thousands and thousands of bucks yearly that pass into the overall faculty fund.

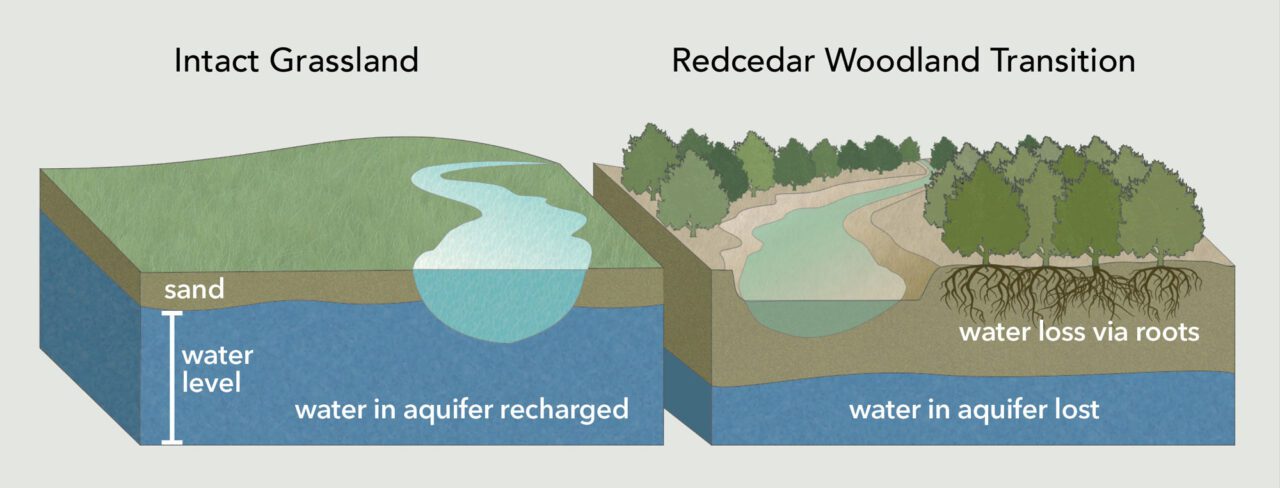

The redcedars even threaten the bountiful Ogallala Aquifer. Forests are thirstier than grasslands, sucking up floor and shallow groundwater.

“This impacts each citizen that lives within the Nice Plains,” says Twidwell.

The lack of forage and profitability from woody encroachment, he says, has a pernicious impact that hurries up the issue. Ranching survives on reasonably skinny benefit margins, and when earnings decline, the instances are ripe for ranchlands to be transformed into different land makes use of, comparable to row-crop agriculture or building. The full impact is the lack of grass, the lack of grazing, and the lack of a vanishing prairie ecosystem with weak flora and fauna communities.

Says Twidwell, “What we’re seeing is whole ecosystem cave in, [with] surprising penalties in tactics no one would be expecting.”

“No strategy to get on most sensible of it”

As soon as Sarah Sortum and her kinfolk actualized redcedar was once claiming their vary, they attacked with chainsaws, handsaws, loppers, or even a skid-steer in an try to break the invading bushes.

“There was once completely no means lets get on most sensible of it, and it was once additionally relatively dear,” she says. “That’s why we became to prescribed fireplace, which was once in point of fact onerous for my dad, as a result of, culturally, he grew up the place fireplace was once very frightening and dangerous.”

On the outset, Sortum says her kinfolk was once on their very own with enterprise prescribed burns. They didn’t know the place to show for recommendation and strengthen, aside from the agricultural volunteer fireplace division—or even they didn’t need to assist in the beginning.

“We requested if they might pop out and assist, and nearly everyone at the fireplace division didn’t need us to do our fireplace,” says Sortum.

“However they got here out and helped anymeans,” she says. “They weren’t in point of fact in desire of it, however they’re excellent neighbors.”

Quickly after the ones first burns have been finished, the neighbors across the Switzer Ranch belongings took understand of what grew again within the blackened, charred pastures—thick grass and wildvegetation, with out bushes.

“It didn’t take lengthy for our neighbors to seem over the fence to look what it appeared like, and so they pass, ‘Oooh, that appears lovely excellent!’” Sortum says. “They requested us if we might assist them burn.”

Her kinfolk has persevered to burn a number of hundred acres each spring, in order that any given acre will get fireplace each 10 to twelve years. Sortum says she’s inspired by way of the advantages to resident birds.

“Particularly the ones first two years after a hearth, there’ll be a couple of extra forbs that arise than standard … the flowering vegetation that draw within the insects,” Sortum says. “After I pass to these spaces, I swear the ones prairie-chickens and the grouse, they march their broods into the ones spaces in past due July and early August, and that’s the place they carry the ones chicks.”

Greg Gehl is every other Nebraska rancher who, like Sortum, was once surprised to find that redcedar was once poised to overhaul his grazing lands within the japanese Sandhills.

“We discovered impulsively, we’re dropping grass!” Gehl says. “Taxes don’t pass down. Fastened prices don’t pass down. So the place do we need to make that again up? We’ve were given to do away with the cedars!”

As Gehl become extra involved, he were given in contact with Ryan Hotel, the Sandhills running lands coordinator for Pheasants Perpetually, a nonprofit conservation workforce that works for the professionaltection and rehabilitation of grassland habitat for prairie recreation birds. Despite the fact that hired by way of Pheasants Perpetually, Hotel works within the U.S. Division of Agritradition’s Herbal Assets Conservation Carrier place of work within the the city of Neligh, the place he is helping landowners hook up with quite a lot of grant-supported and government cost-share methods, comparable to conservation incentive methods funded throughout the federal Farm Invoice. Hotel helped Gehl expand a plan to overcome again the bushes and open up his grassland.

“What it quantities to is you get a extra holistic solution to control,” says Gehl. “So when cows do excellent, flora and fauna does excellent.”

Gehl started by way of shredding and reducing and piling bushes. Then he presented prescribed fireplace to the ranch.

“Initially we had a hearth division that was once useless set towards burns,” he says. However redcedar modified numerous attitudes. “Over a 10-year duration, we went from a hearth district with two stations that didn’t personal a torch, wouldn’t do a burn. We now personal six torches and do more than one burns a 12 months.”

Nowadays, Gehl is selling fireplace as a vital and loyal instrument for managing rangelands.

“We’re going to need to burn yearly,” he says. “That’s only a reality of lifestyles now. That’s essentially the most economical keep watch over. It’s superb: Individuals who have been useless set towards it, they’ve advanced into serving to.”

Consistent with Gehl, prescribed fireplace provides ranchers some way ahead throughout the thicket of woody encroachment, whether or not their leader worry is for birds or ranching.

“Because the birds go away, so does the grazing,” says Gehl. “For me the birds and the flora and fauna are secondary, staying alive is number one. But when we will be able to supply a complete, wholesome ecosystem, then everyone is worked up. Everyone will have to have the ability to live to tell the tale on that.”

And there’s proof that the burns are running. Within the Loess Canyons—a special prairie landform of bluffs, ridges, and steep gullies simply south of the Sandhills—landowners had been scuffling with bushes for twenty years. Consistent with Fogarty’s analysis on the College of Nebraska–Lincoln, as fireplace killed redcedars and lowered the level of woodlands, grassland fowl species range higher throughout 65% of the Loess Canyons—and a few fowl populations are rebounding dramatically (Northern Bobwhite are up 200%).

“Grassland birds are responding,” says Fogarty. “It’s lovely spectacular what they’re doing there.”

“What’s excellent for the ranch is excellent for the flora and fauna”

Consistent with Ryan Hotel at Pheasants Perpetually, the converting tide of bringing ranchers on board to combat cedars is the important thing to maintaining grassland habitats at the floor in Nebraska.

“Not anything occurs with out landproprietor buy-in,” Hotel says. “I imply, Nebraska is 97% privately owned. We will be able to have the entire cash and the entire methods on the planet, but when we don’t have landowner buy-in, we don’t do anything else. They’re our greatest spouse. They make this occur.”

To foster extra of the ones forms of sectionnerships, the Nebraska Recreation and Parks Fee has a workforce of greater than 20 workers running with ranchers to fund habitat paintings, essentially redcedar elimination, via a mixture of state and federal cash (a lot of it coming throughout the Pittman-Robertson Wildlifestyles Recovery Act, which is funded via taxes at the sale of firearms). The Recreation and Parks Fee works with quite a lot of companions together with The Nature Conservancy, Northern Prairie Land Agree with, and the Santee Sioux Country. However many of the tree elimination and grassland recovery happens on personal land, says fee flora and fauna biologist T. J. Walker.

“In the end the landowners are going to be those who’re going to win this fight,” says Walker. “We’re seeking to assist them get forward of it, however they’re those who’re going to need to care for it and stay on most sensible of it down the street.”

Along the Recreation and Parks Comchallenge, the Sandhills Process Drive—a rancher-led workforce—is securing grants for cost-share methods, offering technical recommendation, and serving to ranchers in finding dependable contractors for casting off and controlling the unfold of bushes. Consistent with Shelly Kelly, the duty drive director, all of it begins with converting entrenched attitudes about fireplace.

“A large number of the ranchers imagine that fireplace is a four-letter F-word within the Sandhills, and that we shouldn’t have any fireplace, so we paintings in point of fact onerous on that fireplace aspect to educate other folks about prescribed burning,” Kelly says. “That it’s very other from wildfire, and that during some spaces it’s in point of fact the most efficient solution for controlling this.”

The duty drive groups up with The Nature Conservancy to expand prescribed burn plans and teach landowners in the usage of fireplace. A flora and fauna biologist is desirous about growing every burning plan to ensure “all of our initiatives have a flora and fauna center of attention,” says Kelly.

“We’re blessed to reside in a space the place what’s excellent for the ranch is excellent for the flora and fauna,” she says. “The prairie-chickens and the grassland birds want open and intact grasslands. The similar means with the cows.”

And in line with Kelly, the destiny of the prairie is determined by that dating between ranchers and grasslands: “If we lose our land stewards, we’re going to lose the stewardship that is going along side them.”

Sortum consents. If ranchers don’t reach conserving the prairie, she doesn’t know who will step up. Struggling with redcedar has turn into “a part of how we do trade now.” With out the vested interest of ranchers in maintaining the grasslands open, no different workforce might be keen or in a position to spend the cash had to combat a relentless fight with bushes.

“That’s my actual giant worry. If the land use adjustments and it doesn’t make sense for other folks to stick on most sensible of the issue, they’re going to let it pass and it’s going to develop into a wooded area as an alternative of a grassland,” she says. “It’s in our easiest passion to stay it a grassland.”

Concerning the Creator

Freelance creator Greg Breining is a common contributor to Dwelling Chicken. He writes about wildlifestyles, the surroundings, well being, and science.